Turing machine simulator (C)

From LiteratePrograms

- Other implementations: C | C++ | C++ | Haskell | Java | LaTeX | OCaml | Ruby | Scheme | Sed | Unlambda

We describe a simple C program for simulating an abstract Turing machine. This demonstrates that C is Turing-complete (with the caveat that limitations in word size limit the effective addressable memory).

Contents |

Formal problem description and assumptions

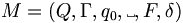

We define a single-tape Turing machine as a 6-tuple  , where

, where

- Q is a finite set of states;

- Γ is the finite tape alphabet (the symbols that can occur on the tape);

-

is the initial state;

is the initial state;

-

is the blank symbol;

is the blank symbol;

-

is the set of accepting (final) states;

is the set of accepting (final) states;

-

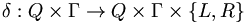

is the transition function which determines the action performed at each step.

is the transition function which determines the action performed at each step.

Initially the tape has the input string on it, followed by an infinite number of blank symbols ( ), and the head is at the left end of the tape. At each step we use the transition function to determine the next state, the symbol written on the tape just prior to moving, and the direction to move the head, left (L) or right (R). If we ever reach a final state, the machine halts.

), and the head is at the left end of the tape. At each step we use the transition function to determine the next state, the symbol written on the tape just prior to moving, and the direction to move the head, left (L) or right (R). If we ever reach a final state, the machine halts.

For simplicity, we will assume that the tape alphabet has the fixed size 28 = 256. This does not affect the power of the machine, but does make it more convenient to implement in a byte-oriented language. We will also assume for convenience that the number of states does not exceed the word size; this does affect the power of the machine, but because C does not provide an arbitrary-precision integer object, it would be tedious to do otherwise. Also, this provides enough states for most practical Turing machine programs.

Main simulator

State representation

We will represent each state and each symbol with a simple integer type. The alphabet size is fixed at 256, so a single-byte char type is suitable for representing a symbol:

<<constants>>= #define TAPE_ALPHABET_SIZE 256 <<type definitions>>= typedef char symbol;

We represent the state of the machine at a single instant using the following structure, which describes the tape contents, the current control state, and the current position of the head on the tape:

<<Turing machine state structure>>= struct turing_machine_state { int control_state; int head_position; int tape_size; symbol* tape; };

We can update this structure based on what the transition function tells us to do. It supplies a new control state, a character to write, and a direction in which to move the head:

<<type definitions>>= enum direction { DIR_LEFT, DIR_RIGHT }; <<state update function>>= void update_state(struct turing_machine_state* state, int new_control_state, enum direction dir, char write_symbol, char blank_symbol) { state->control_state = new_control_state; state->tape[state->head_position] = write_symbol; if (dir == DIR_LEFT && state->head_position > 0) { state->head_position--; } else { /* dir == DIR_RIGHT */ state->head_position++; } expand tape if needed }

Note that the head is prevented from moving off the left end. Because we can't actually allocate an arbitrary-sized tape, we allocate a tape of a fixed size and dynamically expand it if the head moves past the right end, filling in the new cells with blank characters:

<<expand tape if needed>>= if (state->head_position >= state->tape_size) { int i, old_tape_size = state->tape_size; symbol* new_tape = realloc(state->tape, old_tape_size*2 + 10); if (new_tape == NULL) { printf("Out of memory"); exit(-1); } state->tape = new_tape; state->tape_size *= 2; for (i=old_tape_size; i < state->tape_size; i++) { state->tape[i] = blank_symbol; } }

The various system calls above require stdlib.h, stdio.h, and string.h (memmove):

<<header files>>= #include <stdlib.h> #include <stdio.h> #include <string.h>

We also need a way to create an initial machine state, given the initial control state and input string. We allocate just enough space for the input string, and any characters beyond the end can be assumed to be blank:

<<create initial state function>>= struct turing_machine_state create_initial_state(int initial_control_state, int input_string_length, symbol* input_string) { struct turing_machine_state state; state.control_state = initial_control_state; state.head_position = 0; /* Initially at left end */ state.tape_size = input_string_length; state.tape = malloc(sizeof(symbol)*input_string_length); if (state.tape == NULL) { printf("Out of memory"); exit(-1); } memmove(state.tape, input_string, sizeof(symbol)*input_string_length); return state; }

Since this performs allocations, we need a function to deallocate these resources when we're done with the state object:

<<free state function>>= void free_state(struct turing_machine_state* state) { free(state->tape); }

For diagnostic purposes, it's also useful to print out some of the details of a state. We only show the first TRACE_TAPE_CHARS characters of the tape:

<<constants>>= #define TRACE_TAPE_CHARS 78 <<trace state function>>= void trace_state(struct turing_machine_state* state, symbol blank_symbol) { int i; for(i=0; i < TRACE_TAPE_CHARS && i < state->head_position; i++) { printf(" "); } if (i < TRACE_TAPE_CHARS) { printf("v"); /* points down */ } printf("\n"); for(i=0; i < TRACE_TAPE_CHARS; i++) { printf("%c", i < state->tape_size ? state->tape[i] : blank_symbol); } printf("\n"); } <<header files>>= #include <ctype.h>

This completes the set of state manipulation functions:

<<state functions>>= create initial state function free state function state update function trace state function

Machine representation

Since we're representing states and characters with integers, Q and Γ need no explicit representation. This structure represents the remaining information about the machine:

<<Turing machine structure>>= struct turing_machine { int initial_control_state; char blank_symbol; int num_accepting_states; int* accepting_states; struct transition_result** transition_table; };

The last item is a two-dimensional array of transition_result objects, indexed by the current symbol under the tape head and the current control state. The transition_result structure represents the three-tuple range of the transition function used to produce the next state:

<<Transition function result structure>>= struct transition_result { int control_state; symbol write_symbol; enum direction dir; };

Our choice of a two-dimensional array for the transition function makes the resulting code simple, but tends to be very wasteful of space in practice since most Turing machines are sparse (most transitions just cause it to reject immediately). A denser representation, such as the adjacency list representation of the state graph, would be more practical. (The state graph is the directed graph where each vertex is a state and each edge is labelled with an input character, an output character, and left/right).

Simulation

We now come to our primary public simulation function. Using our machine state functionality, we can take a turing_machine structure and an input string and step through successive states:

<<simulate function>>= void simulate(struct turing_machine machine, int input_string_length, symbol* input_string) { struct turing_machine_state state = create_initial_state(machine.initial_control_state, input_string_length, input_string); state tracing initial while (!is_in_int_list(state.control_state, machine.num_accepting_states, machine.accepting_states)) { struct transition_result next = machine.transition_table[state.control_state] [(int)state.tape[state.head_position]]; update_state(&state, next.control_state, next.dir, next.write_symbol, machine.blank_symbol); state tracing } free_state(&state); } <<public declarations>>= void simulate(struct turing_machine machine, int input_string_length, symbol* input_string);

We'll talk about state tracing when we discuss the test driver. The is_in_int_list() helper function just does a linear search on a list of ints:

<<is_in_int_list function>>= int is_in_int_list(int value, int list_size, int list[]) { int i; for(i=0; i<list_size; i++) { if (list[i] == value) { return 1; } } return 0; }

This may be a bottleneck for machines with many accepting states, in which case it could be replaced with a more efficient set data structure.

Files

Finally, we put it all together into a header file and a source file, using the usual idiom to avoid multiple inclusion of the header:

<<simulate_turing_machine.h>>= #ifndef _SIMULATE_TURING_MACHINE_H_ #define _SIMULATE_TURING_MACHINE_H_ constants type definitions Transition function result structure Turing machine structure public declarations #endif /* #ifndef _SIMULATE_TURING_MACHINE_H_ */ <<header files>>= #include "simulate_turing_machine.h"

<<simulate_turing_machine.c>>= header files Turing machine state structure /* This structure need not be public */ state functions is_in_int_list function simulate function

This completes the simulator implementation.

Test driver

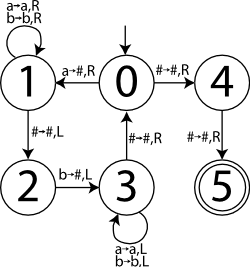

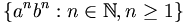

To test the simulation, we'll implement the simple Turing machine shown to the right, which is based roughly on this Turing machine example. This diagram is a state graph, meaning that each vertex represents a state in the machine's finite control, and each edge indicates the input character that must be read to follow that edge, the character to write over it, and the direction to move the head. The initial state is 0 and the only accepting state is 5. It recognizes the following context-free but nonregular language:

The pumping lemma says that this is nonregular, but a Turing machine to recognize it is fairly straightforward. Here's how we construct a Turing machine object for it:

<<Example turing machine producer>>= struct turing_machine get_example_turing_machine(void) { struct turing_machine machine; int i, j; machine.initial_control_state = 0; machine.blank_symbol = '#'; machine.num_accepting_states = 1; machine.accepting_states = malloc(sizeof(int)*machine.num_accepting_states); if (machine.accepting_states == NULL) { printf("Out of memory"); exit(-1); } machine.accepting_states[0] = 5; initialize transition table return machine; }

We need headers for the malloc() and printf():

<<test headers>>= #include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h>

Initially, all entries of the transition table point to a special state STATE_INVALID not shown in the diagram. If this state is reached, the input is not in the language:

<<initialize transition table>>= #define NUM_STATES 7 #define STATE_INVALID 6 machine.transition_table = malloc(sizeof(struct transition_result *) * NUM_STATES); if (machine.transition_table == NULL) { printf("Out of memory"); exit(-1); } for (i=0; i<NUM_STATES; i++) { machine.transition_table[i] = malloc(sizeof(struct transition_result)*TAPE_ALPHABET_SIZE); if (machine.transition_table[i] == NULL) { printf("Out of memory"); exit(-1); } for (j=0; j<TAPE_ALPHABET_SIZE; j++) { machine.transition_table[i][j].control_state = STATE_INVALID; machine.transition_table[i][j].write_symbol = machine.blank_symbol; machine.transition_table[i][j].dir = DIR_LEFT; } } insert nontrivial transitions

We then add entries for each arc in the diagram:

<<insert nontrivial transitions>>= machine.transition_table[0]['#'].control_state = 4; machine.transition_table[0]['#'].write_symbol = '#'; machine.transition_table[0]['#'].dir = DIR_RIGHT; machine.transition_table[0]['a'].control_state = 1; machine.transition_table[0]['a'].write_symbol = '#'; machine.transition_table[0]['a'].dir = DIR_RIGHT; machine.transition_table[4]['#'].control_state = 5; machine.transition_table[4]['#'].write_symbol = '#'; machine.transition_table[4]['#'].dir = DIR_RIGHT; machine.transition_table[1]['a'].control_state = 1; machine.transition_table[1]['a'].write_symbol = 'a'; machine.transition_table[1]['a'].dir = DIR_RIGHT; machine.transition_table[1]['b'].control_state = 1; machine.transition_table[1]['b'].write_symbol = 'b'; machine.transition_table[1]['b'].dir = DIR_RIGHT; machine.transition_table[1]['#'].control_state = 2; machine.transition_table[1]['#'].write_symbol = '#'; machine.transition_table[1]['#'].dir = DIR_LEFT; machine.transition_table[2]['b'].control_state = 3; machine.transition_table[2]['b'].write_symbol = '#'; machine.transition_table[2]['b'].dir = DIR_LEFT; machine.transition_table[3]['a'].control_state = 3; machine.transition_table[3]['a'].write_symbol = 'a'; machine.transition_table[3]['a'].dir = DIR_LEFT; machine.transition_table[3]['b'].control_state = 3; machine.transition_table[3]['b'].write_symbol = 'b'; machine.transition_table[3]['b'].dir = DIR_LEFT; machine.transition_table[3]['#'].control_state = 0; machine.transition_table[3]['#'].write_symbol = '#'; machine.transition_table[3]['#'].dir = DIR_RIGHT;

We don't bother deallocating anything since this structure lives for the lifetime of the process. Now, we simply invoke the simulate function on this structure, allowing the user to specify the initial input on the command line in argv[1]:

<<test_driver.c>>= test headers #include <string.h> #include "simulate_turing_machine.h" Example turing machine producer int main(int argc, char* argv[]) { if (argc < 1 + 1) { printf("Syntax: simulate_turing_machine <input string>\n"); return -1; } simulate(get_example_turing_machine(), strlen(argv[1]), argv[1]); return 0; }

If we run the program on a string in the language, like "aaabbb", the program will return quickly; otherwise it will freeze, indicating it's entered the invalid state. To ensure it's going through the right intermediate states, we add some tracing to the simulate() function to print out the state:

<<state tracing initial>>= trace_state(&state, machine.blank_symbol); <<state tracing>>= trace_state(&state, machine.blank_symbol);

Now we can see, for example:

<<example_output.txt>>= $ simulate_turing_machine ab v ab############################################################################ v #b############################################################################ v #b############################################################################ v #b############################################################################ v ############################################################################## v ############################################################################## v ############################################################################## v ##############################################################################

See Turing machine simulator (C)/Example output for a longer example output.

| Download code |